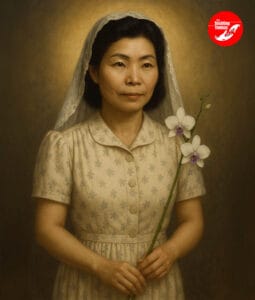

Early Life, Family, and Formation

Masue Masuda was born to well-to-do merchant parents in Japan. Her early years were marked not by rootedness but by movement and education. She spent part of her youth in Perth, Australia, and later in Nagasaki, Japan—an upbringing that exposed her early to cultural diversity and languages. Raised in a Buddhist household, she absorbed values of discipline, restraint, and compassion that would later find striking resonance with Christian virtues.

Well educated and intellectually gifted, Masue trained as a teacher (sensei), a vocation held in high esteem in Japanese society. This profession would later become both her protection and her instrument of mercy. Eventually, at the request of remaining family members, she traveled to Davao, Philippines. There, her life took a decisive turn.

Love, Marriage, and a New Homeland

In Davao, Masue met Vicente Almazan, a fellow teacher. Their affection deepened quickly, but cultural and familial opposition—particularly to a Japanese-Filipino union—forced them to marry quietly. Choosing love over comfort, the couple eventually settled in San Narciso, Zambales, Vicente’s hometown, where they raised eight children as humble farmers.

Masue embraced local life with remarkable humility. Though Japanese by birth, she learned Ilocano, lived simply, and identified deeply with the Filipino people. She was no longer a visitor, but a wife, mother, and neighbor in a small coastal town that would soon be engulfed by war.

Intertwined Lives Before the War

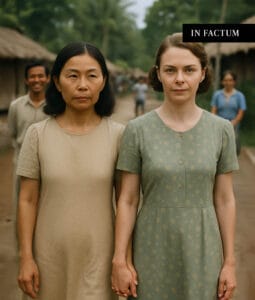

In San Narciso, Masue formed close bonds with two other foreign women married to Filipinos: Nellie Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas, an American Catholic, and Mary Nakashima-Evangelista, a fellow Japanese. Their friendship began in ordinary domestic life—shared concerns of family, teaching, and community—but deepened dramatically as the shadow of war loomed.

Elizabeth Stocks and Mary Nakashima were Catholics; Masue was Buddhist. Yet religious difference did not hinder intimacy. Mutual respect, trust, and shared concern for their adopted community anchored their friendship, preparing them—unknowingly—for the extraordinary trials ahead.

War, Widowhood, and Heroic Mercy

When World War II reached the Philippines, Masue’s mother warned her in a letter to return to Japan. She refused, choosing instead to remain with her husband and children. That decision would cost her dearly.

Because of her profession and multilingual abilities, Masue became the natural choice of the Kempeitai—the feared Japanese military police—as interpreter in San Narciso. Officially, she served the occupying forces. In reality, she worked quietly and relentlessly to save Filipino civilians and guerrilla fighters from torture and execution. Using Japanese, English, and Ilocano, she turned language itself into a shield—fabricating explanations, softening accusations, and crafting narratives that secured prisoners’ release.

Tragedy struck in 1942 when Vicente Almazan was shot dead in his own home amid tensions between guerrilla forces and Japanese-associated families. Grief might have hardened her heart; instead, Masue chose mercy. When a 14-year-old guerrilla recruit, Rafael Falucho, begged forgiveness for his role in the killing, she granted it without hesitation, seeing him as another victim of war’s machinery.

She refused revenge. She refused zoning raids. She refused to let hatred claim another life through her grief. She pleaded for prisoners, mitigated accusations, served as guarantor for families marked for execution, and repeatedly intervened for Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas herself—even as intelligence reports continued to identify Elizabeth as a guerrilla leader. When bounty hunters nearly massacred the Fontillas family in Paite, Masue personally vouched for them, shielding them under her own name and reputation.

To survivors like Modesto Ferdivilla, who returned to thank her after escaping death, she redirected praise to God alone and urged a life of gratitude and faith. When Elizabeth Stocks was released from the Iba garrison—her foot smashed by a Japanese soldier’s rifle butt—it was Masue who stood ready to welcome her home once more.

When American forces arrived, liberation for Filipinos meant danger for Japanese families. Yet the people of San Narciso did not forget her courage. Those she had saved protected her in return, helping her family escape retaliation.

Forgiveness Answering Forgiveness

At liberation, roles reversed. Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas, now wearing an American captain’s uniform, encountered the soldier who had crippled her. Expecting execution, he instead received forgiveness. Elizabeth assured his safe return to Japan.

Masue, too, continued to forgive. She forgave those who falsely accused her of being a Japanese spy before the war—an accusation that led to her long interrogation at Fort Stotsenberg and to her absence from home when her youngest child, Chita, died of measles due to wartime shortages. Above all, she forgave Rafael Falucho.

The First Marian Apparition (During the War)

It was during this period of unbearable strain that Masue experienced the first of three alleged Marian apparitions.

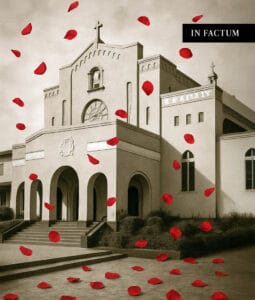

After one particularly harrowing day serving as interpreter during brutal interrogations, she took a shortcut home along the churchyard of St. Sebastian Church. Suddenly, the night erupted in light—brighter, she said, than a thousand bulbs. Atop the church tower stood “the most beautiful Lady.”

Masue fell prostrate and remained there for nearly two hours. When the vision ended, dawn was already breaking.

Still a Buddhist, she confided only to a close friend that her death might be near, believing Heaven had visited her. Yet instead of fear, she felt profound peace. That calm strengthened her resolve to continue saving lives. The encounter became an unseen wellspring of courage throughout the remainder of the war.

The Second Apparition

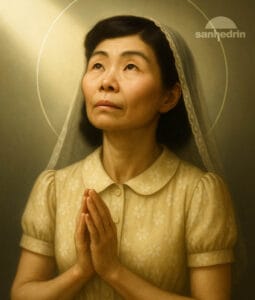

After the war, Masue’s life grew materially poorer but spiritually deeper. She was baptized at St. Sebastian Church, taking the name Elizabeth in honor of her beloved friend Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas. Though Vicente had been Aglipayan, Masue chose Catholicism and had all her children baptized as Catholics.

Her conversion was not born of convenience, but of years of contemplation, heroic forgiveness, and the lingering presence of the Lady she had once seen. Catholicism gave sacramental meaning to what she had already lived.

The second apparition occurred during Misa de Gallo. While gazing at the Belen, Elizabeth appeared transfixed. Those nearby noticed her kneeling in intense reverence, as if the Blessed Virgin had stepped out of the Nativity scene itself. Behind her stood a man described as having “the kindest countenance ever.”

The Third Apparition

Elizabeth lived the rest of her life in stark poverty. Deprived of her rightful share of Vicente’s land, she supported her children by selling vegetables. Her clothes were patched repeatedly; nothing was wasted. When a substantial monetary reward was raised to honor her wartime heroism, she refused it, believing she had merely prevented her countrymen from becoming oppressors.

Near the end of her life, weakened by illness yet marked by serenity, a third apparition reportedly occurred. One night, feeling unexpectedly strong, she rose to fetch water. Near a young caimito (star apple) tree, the Blessed Virgin appeared atop one of its branches and told her that her sins were forgiven and that she would soon join her in Heaven.

Two weeks later, Elizabeth gave her remaining five-peso bill to her daughter Presentacion, saying she did not wish to bring anything worldly where she was going.

She died in 1953, just eight years after the war.

A Final Testimony of Friendship

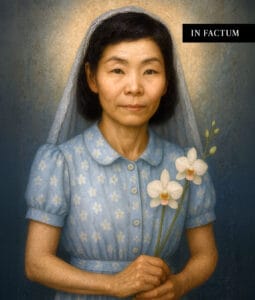

When Masue died, Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas undertook a painful 1.7-kilometer journey, crippled and limping, leaning on her youngest son John as her support. She carried two orchid stalks—flowers Masue dearly loved.

When she placed them upon Masue’s coffin, the glass covering broke, allowing the flowers to fall upon Masue’s chest. Those present wept and exclaimed that Masue had accepted her friend’s gift with her heart—a fitting final sign of two lives forever intertwined.

Legacy

Elizabeth Masue Masuda-Almazan saved hundreds of lives, crossed boundaries of race and nation, and embodied mercy in an age of cruelty. Though absent from textbooks, her memory remains alive in San Narciso, Zambales, and among her descendants.

Many miracles, including medically inexplicable cures, are attributed to her intercession. Yet some lament the caution or indifference of authorities, suspecting that cultural bias may have muted wider recognition of her sanctity.

Her life reveals that holiness often grows quietly. Together with Elizabeth Stocks-Fontillas, she stands as a living catechesis on ecumenism, forgiveness, and seeing Christ in the other. Even as a Buddhist, she aligned herself with Christ, the Cornerstone, through mercy and self-giving love.

As St. Paul wrote: “You are no longer aliens or foreign visitors… but members of God’s household” (Eph. 2:19–22).

Like Nathanael’s question—“Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”—her story invites another: Can anything holy come out of San Narciso? Those who know the story of the Lady on the church tower and the star apple tree already know the answer.